Immediately after Christmas, writing from the family home on Castle Square, Southampton, there are beans to spill:

The widgeon and the preserved ginger were as delicious as one could wish. But as to our black butter, do not decoy anybody to Southampton by such a lure, for it is all gone. The first pot was opened when [brother and sister-in-law] Frank and Mary were here, and proved not at all what it ought to be; it was neither solid nor entirely sweet, and on seeing it, Eliza remembered that Miss Austen had said she did not think it had been boiled enough. It was made, you know, when we were absent. Such being the event of the first pot, I would not save the second, and we therefore ate it in unpretending privacy; and though not what it ought to be, part of it was very good.

It was a paste of berry fruits, reduced with sugar (but no butter), to be spread on bread as a richer kind of jam. Poor Eliza has taken her eye off the boil with this batch, but waste not, want not. Like the Victorian curate's egg, it was at least good in parts.

Details of food and drink in Jane Austen's Letters are as remarkable for their discrimination and wholesale enjoyment as they are freighted with moral significance in her novels. Ten years before, writing from lodgings at the Bull and George in Dartford, Jane reported to her sister that 'We sat down to dinner a little after five, and had some beef-steaks and a boiled fowl, but no oyster sauce'. Was the absence of oyster sauce regretted, or does it betoken a stern refusal? Not today, thank you.

The Georgian society into which Jane was born in December 1775 leaves a lightly but finely detailed imprint on her novels. They represent indeed a brief transitional passage that would dissolve the racketing metropolitan milieu of Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett in an ethos of mannered Regency gentility and vertiginous social decorum, where the affiances are painstakingly negotiated and emotions adroitly checked. Somewhere offstage, the European mainland is convulsed by the Napoleonic Wars, but at Bath and Lyme Regis, we take the air, make house calls, insist on the calm civility that will have to fill out the picture again anyway when the muskets fall silent.

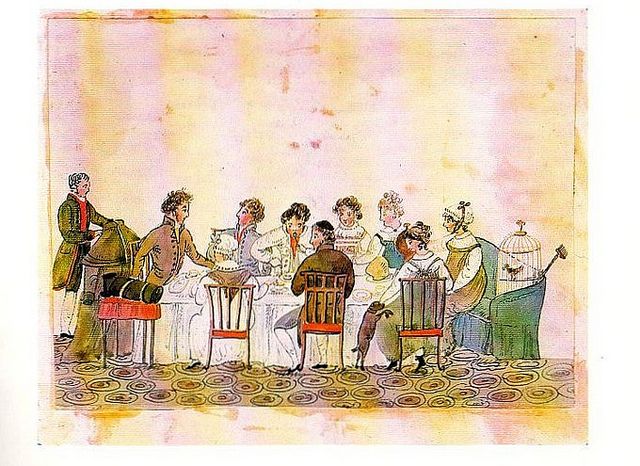

| From: Mrs. Hurst Dancing & Other Scenes from Regency Life, Diana Sperling 1812-1823 by Gordon Mingay, 1981. |

Nor was there need to wait for Brillat-Savarin to arrive at the perduring wisdom that we are what we eat, and even more so what we decline. Emma Woodhouse's father already knows it well enough to make a meal an obstacle-course of hazards. 'He loved to have the cloth laid … but his conviction of suppers being very unwholesome made him rather sorry to see anything put on it.' Urging a soft-boiled egg on his lady guests, he reassures them that the eggs are vanishingly small. While one might take a tiny morsel of apple tart, 'I do not advise the custard'. As to intoxicating matter, one can scarcely be too careful. 'Mrs Goddard, what say you to half a glass of wine? A small half-glass – put into a tumbler of water?'

Between frugality and refinement, the line is perilously thin. When Elizabeth Bennet sits down to dinner at the Bingleys' country estate, Netherfield Park, in Pride and Prejudice, she finds the conservatism of her own tastes counts against her. Her immediate neighbour at table is the husband of one of the Bingley sisters, a Mr Hurst, 'who lived only to eat, drink, and play at cards … [W]hen he found her prefer a plain dish to a ragout, he had nothing to say to her'. Ragout was well on its way at this era to being a continental signifier of all that was decadent in the moral economy of taste. It was rich, highly seasoned, a thorough denaturing of all that was wholesome and honest in British preference, which disdained the over-adornment of meat, other than in the sneering pretention of a Mr Hurst.

'When Marianne's heart breaks, Mrs Jennings prescribes food and drink – dried cherries, sweetmeats, olives, a glass of particularly good Constantia'

What stood in the place of cultivated gourmandising was simple heartiness of appetite, hardly more eloquently represented anywhere in Austen than by the meddlesome but cheering Mrs Jennings in Sense and Sensibility. A lady of corpulent appetites, she is something of an embarrassment to the fastidious Dashwood sisters, with her rapturous talk of stuffing down the mulberries on an idyllic day of picking. Luring the Dashwoods to her house in London, she frets over their careless indifference in the matter of eating en route, 'only disturbed that she could not make them choose their own dinners at the inn, nor extort a confession of their preferring salmon to cod, or boiled fowls to veal cutlets'. When Marianne's heart breaks, Mrs Jennings prescribes food and drink – dried cherries, sweetmeats, olives, a glass of particularly good Constantia, the legendarily luscious Cape Muscat, unfortified in those days, but no less of a tonic for repining girls.

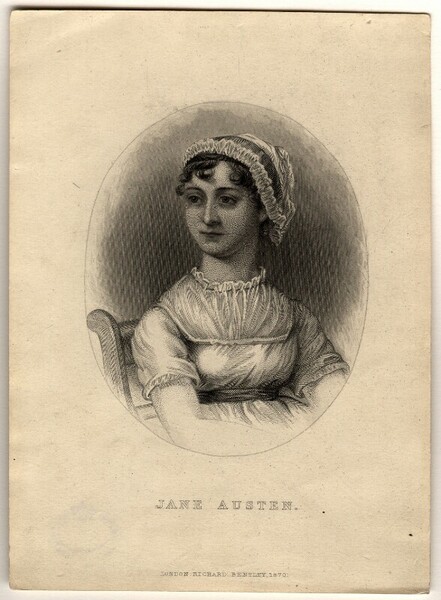

Jane Austen published by Richard Bentley, after Cassandra Austen. Stipple engraving, published 1870 NPG D1008 © National Portrait Gallery, London

If food can be an indicator of the wrong state of mind, as it is to Mr Woodhouse and Mr Hurst, it is also, as emerges from the numerous references to it in Jane's letters, at the heart of the best kinds of sociability, the togetherness of reconciled human relations, and indispensable to festivity. In the Christmas episode on the Musgroves' country estate, Uppercross House, in her last completed novel, Persuasion, it is sufficiently eloquent of domestic happiness to be a prefiguration of the wholesale Yuletide mythology of the Cratchit family's Christmas Day in Dickens: 'On one side was a table occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others.'

Restaurants on the Jane Austen trail

Menu Gordon Jones, Bath

Boutique restaurant teeming with personality. No menu, at least not one you'll see, but plenty of riotously inventive modern British cooking, the perfect end to a day spent exploring the Regency city to which George Austen moved his family, including Jane, in 1800. Read our full review of Menu Gordon Jones here.

Upstairs at Landrace, Bath

Above the bakery is an all-day venue that opens for coffee and fresh bakes first thing, with inspired contemporary bistro cooking to follow at lunch and dinner. Read our full review of Upstairs at Landrace here.

Lilac, Lyme Regis

Situated in a 400-year-old basement in the Dorset resort to which Captain Wentworth takes Anne Elliot and the Musgroves in Persuasion, Lilac offers Italianate cutting-edge cooking with the emphasis on sustainability, eco-sourcing and zero waste. It will be closing permanently on 3rd August, so get there soon. Read our full review of Lilac here.

Pompette, Oxford

When she was only seven years old, Jane and her elder sister Cassandra were packed off to Oxford to begin their education. Pascal Wiedemann's modern French spot in tranquil Summertown boasts an outdoor terrace, with petit déjeuner, steak frîtes and bushels of bonhomie française. Read our full review of Pompette here.

Marmo, Bristol

Big cities don't make much of an impression on Jane's fictional world, but the Bristol that forms a backdrop in outline to parts of Northanger Abbey and Emma is now one of England's premier gastronomic destinations. You could do a lot worse than start at Marmo, not far from the Lower Avon, with its hang-loose small-plates approach and offbeat wines. Read our full review of Marmo here.