Scottish seafood is heralded as some of the world’s best. Exported across Europe and beyond, championed on top restaurants menus, the picture in the mind’s eye is of crystal-clear lochs, unspoilt landscapes and bountiful catch. But the reality of the situation is much murkier.

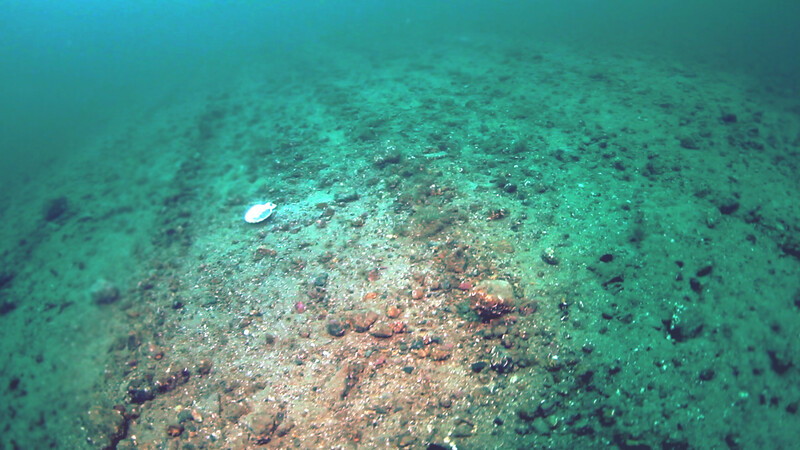

Catastrophically damaging bottom trawling and dredging dominate the fishing industry leaving behind bare sea beds of sand, gravel and the detritus of crushed shellfish. While many chefs and restaurants lead the charge on land with responsibly reared meat and regeneratively grown produce, obscure supply chains, fraught politics and an out-of-sight-out-of-mind complacency dominates the seas.

As part of Sustainable Gastronomy Week, we’re sitting down with Open Seas campaigners Andrea Ladas and Phil Taylor to talk about sweet Scottish scallops and why chefs and diners should choose dived over dredged.

Hand diving is a highly selective, skilled process. Divers can go down to a maximum depth of 50m and literally chose the best by hand. There’s no bycatch and the habitat remains intact. They’re always landed live and sold in their shell, entering kitchens in the most pristine condition possible.

On the other hand, scallop dredging is known to be the most damaging form of fishing that takes place in European seas. Metal chain bags attached to bars, of which there might be several on each side of the boat, are dragged along the sea bed with teeth up to 10cm long which literally rake up the sea bed. It’s very heavy equipment and a very fuel intensive process.

'It’s like harvesting chickens, breaking the legs of some and leaving them behind'

As well as inevitable bycatch in the chain bags, there’s the unrecorded bycatch of broken scallops and crabs left in the wake of the machinery. You don’t need to be a marine biologist to understand the habitat destruction on the sea floor. You can literally visualise it. As Pam [Brunton, chef and co-owner of Inver restaurant] said in the Orkney Dive film, you wouldn’t put up with this on land. It’s like harvesting chickens, breaking the legs of some and leaving them behind…

Would a diner notice the difference on the plate?

What people want from scallops is their sweetness and their buttery texture. With dived scallops you get a concentration of sweet flavour.

With dredged scallops there’s no guarantee that they're landed live because they've been dragged along the sea bed. The shells get broken and they’re often very gritty because the machinery churns up the sea bed. Then they have to be processed back on land: shucked to remove broken shells, de-gritted and sometimes washed with chlorine, or frozen with excess water.

And that’s not to mention the stress to the scallop, which does play a part in the texture. Between the stress and the additional processing, elements of their flavour are lost along the way.

Often you see ‘Orkney scallop’ on restaurant menus. Does that mean hand dived? What’s happening there?

Orkney’s a rare success story. More than 50% of scallops landed there are hand dived [compared to about 4% across Scottish waters] and it’s down to a mix of favourable factors.

Firstly, there’s the geography. It’s far enough from the mainland that nomadic dredgers consider the trip to Orkney too expensive. The costs of running a dredging business are very high, so that matters – it’s much better for a dredging fleet to be based where they can reach more places.

Orkney also has a really good habitat for scallops and for diving. It just so happens that scallop diving was first established here. It’s nice and shallow and the fact that the habitat remains largely intact means its more productive. They grow quickly.

Then there’s the distribution part, which is so fundamentally important – particularly in Scotland – in dictating how the entire fishing industry operates. In Orkney, the hand dived market has largely shaped the supply chain, while elsewhere, someone that owns five trawl boats might also own the processing centre and the means of distribution. It stops small scale fishermen, who rely on those supply chains, from speaking out about the problems with dredging.

This issue doesn’t exist in the same way in England where there are better access routes. You can quite easily courier a couple of boxes from Plymouth but in parts of Scotland there’s no courier passage; you have to get into the consignment with all the other products. And you have to play ball with the guys who’re doing that.

In Orkney, the community has seen hand diving working well and has fought hard to keep it. There’s a bit of peer pressure, and when dredgers come in – which they do – the locals are not happy about it. Hand diving has created more employment, and the development of its reputation has led to increased monetary value and a more robust economy.

Are scallops from other parts of Scotland just as good?

The Hebridean islands produce beautiful scallops of the same species. In some ways Orkney is just a brand name, like in the 80s when people thought only French wine was the best. The West Coast has good community conditions and the potential for habitats to develop further. Hand diving is already more than 10% of the total caught there and we need consumers to be interested – are they from Barra, from Mull? – to support this growth.

If we’re successful, there’s so much more potential for hand diving. Take Ullapool: there’s a Marine Protected Area there meaning only small-scale trawlers are allowed into a couple of areas – the rest is closed to dredging and trawling. The divers there are having a fantastic time. All our efforts are pro-fish, pro-jobs, pro community and pro-environment. We’re also pro-taste!

What can consumers do to help?

It’s so difficult to make decisions about sustainable seafood with the information that’s generally provided. Just choosing a species doesn’t work. You need to know the catch method and where it was landed.

'No one wants to write "dredged scallops" on their menu'

We want consumers to ask the question: ‘are your scallops hand dived?’ The price on the menu might be an indicator, sweetness can be too, but really the only way to know is to ask. Restaurants that do include catch method on their menu are the ones serving hand dived scallops; no one wants to write ‘dredged scallops’ on their menu. Dredged is a bad word. But then, why are we allowing a form of fishing with a story that, collectively, we don’t like?

If you ask the staff in a restaurant, they might go back to the kitchen to check, then the chef might check with the head chef, who might need to check with the supplier. Your question will have an impact.

To find out more about Open Seas’ crucial work to secure a sustainable future for Scotland’s marine life and fishing industry, head here, or lend your voice to their petition to reintroduce a vital inshore limit.