Opened as a hotel in 1958, and first included in the Guide in 1961, you might have thought that this vision of Elizabethan enchantment and Victorian horticultural innovation would go on forever, but Gravetye Manor almost succumbed in 2010 as the financial plague reaped its harvest. Thankfully, the prospect of losing such a beloved friend was too much for one devoted customer – who stumped up the money and saved the day.

1961-1962

This is an unusually lovely house, partly Elizabethan, finely placed in its own large grounds at the end of an inordinately long drive, and quite difficult to find. It is not at Turner's Hill, but on a crossroad joining B.2110 and B.2028, between East Grinstead and West Hoathly. The anxiety of finding it is calmed by the soothing surroundings, and also by the fine wines and good food. No table-d'hôte; à la carte, try the crêpe de fruits de mer (14/-), tropical fruit salad, roast duck (13/6) or tournedos cacciatoria (14/6). The wine list (conditional and club licence) is remarkable; it is very large and effectively that of the Gore Hotel at Kensington, with which this is linked. For a special dinner, the host ordered Château Fuissé '55 (21/-); Ch. Pichon-Longueville Baron (C.B.) '48 (31/6), Ch. Rieussec '55 (25/-), and Sandeman 1896 (55/-), all of which were superb and superbly served. Open all year. Booking essential. Bed and breakfast from 35/- to 45/-. (App. Miss E. Young- hughes; F. L. Attenborough; Mrs. F. N. Taylor; Miss W. F. Shand; John Chapman; N. D. Mussett; Raymond Thompson.)

2022

The house was bought in 1884 by William Robinson, renowned horticulturist, journalist and champion of 'natural gardening', and over the years its grounds have been lovingly nurtured by Gravetye's successive occupants. It's a glorious spot and well worth a wander if time and weather allow; check out the magnificent Victorian kitchen garden if you want to see where many of the ingredients on your plate come from. There are glasshouses and polytunnels on the land as well. It's the kind of place where you're greeted outside by smiling staff and offered drinks out on the lawn or in a grand panelled room with an ornate moulded ceiling; once you're seated in your well-upholstered chair in the smart, contemporary dining room with its wall of glass overlooking blooming borders, everything is hunky-dory – and the feel-good mood continues as the food arrives. A cheese and truffle gougère disappears in one satisfyingly bite, and its companion amuse-bouche – duck liver parfait with blackberry gel – reveals the kitchen's penchant for prettiness. Seasonal lunch and dinner menus include supplementary intermediate courses and cheese if you're going all in, and there are thoughtfully put together vegetarian and vegan opportunities too. The bread basket overflows with the likes of buttermilk brioche and seeded malt bread, although the arrival of five flavoured butters maybe suggests that the kitchen is a little too keen to impress. To follow, cured chalk stream trout gets a sweet smokiness from the clever use of lapsang souchong tea (plus a citrus zing from finger limes), while the Gravetye garden salad with confit egg yolk is a 'beautifully colourful' beatification of the garden's bounty. Modern ideas are underpinned by classical good sense, so 'duck and orange' matches tender meat (its skin deliciously crisp) with a sweet hit of marmalade plus earthy forms of beetroot and red chicory (from caramelised to pickled). Saucing is on the money throughout (Chardonnay with fillet of turbot, for example) and flavours ring true – not least the 'fabulous' mint ice cream, which tastes fresh from the plant and is ceremonially placed into a perfectly risen blackcurrant soufflé. The wine list has the English southern counties covered, including top-drawer fizz, but it deals in excellence from around the world – although its first love is the French classics.

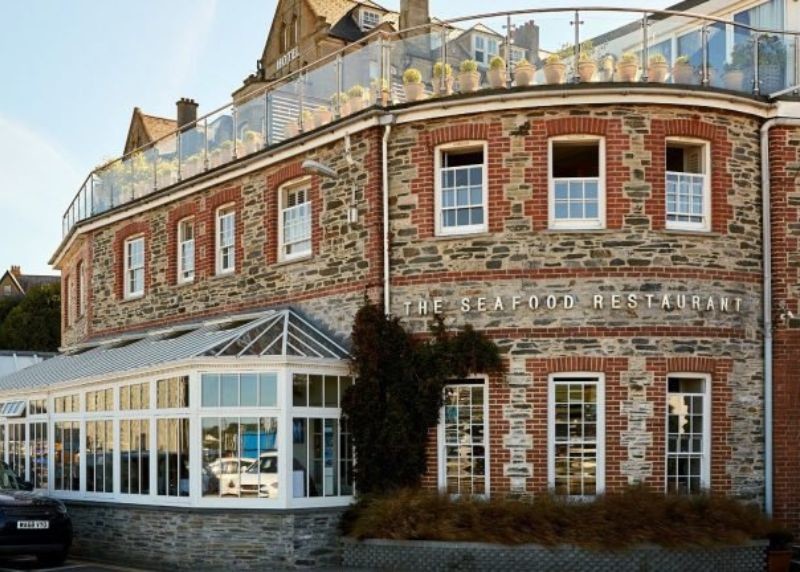

Perhaps the most famous seafood restaurant in Britain first appeared in The Good Food Guide in 1984, although it all began in 1975, with the launch of this former nightclub overlooking the local quayside. As the Guide noted in 1986: ‘It has taken 11 years for the people around Padstow to discover the restaurant’.

1984

Richard Stein became the fish correspondent for Women’s Realm last year, which is unlikely to distract from his main living because this is a serious fish place. Lobsters start at £9, plate of shellfish are £6.95, or there’s a three-course menu at £8.

The dining room is white and well lit. Specialities are bouillabaisse – made without rascasse but with turbot, monkfish, brill, mullet, mussels and langoustines with a saffron liquor – and the local salmon trout, coated in clotted cream and tarragon, wrapped in puff pastry, baked eleven minutes and served with a reduced wine sauce. Fennel is rampant in these parts and he uses it to cure mackerel which is then served with smoked sea trout and mayonnaise.

There are good reports on non-aquatic items such as the watercress soup (’mmmmm’). Meat-eaters get a choice of steak or leg of lamb. The ice creams and sorbets are reliable but the vacherin aux fruits is the star attraction.

The wine list is inexpensive, has an unusually strong showing from a variety of areas and the mark-up’s not greedy. The white Rhônes include Condrieu, Château de Rozay ’80 at £14.85, a mark-up of around 30 per cent. House Sauvignon du Haut Poitou ’81 is £5.05. CELLERMAN’S CHOICE: Fumé Blanc ’79, Robert Mondavi, £11.

2022

Rick Stein gets a lot of stick for transforming Padstow into Padstein, but no one has done as much to persuade Brits to eat the fish hauled from our native waters rather than exporting it all to mainland Europe. True, what was once recognisably a Cornish fishing village is now a chi-chi tourist destination with a Stein venue for every mood and budget, from the casual Rick Stein Café to the dearest of all (in every sense) – his flagship Seafood Restaurant. Long before the TV producers came calling, Stein was a practising seafood cook, who opened this place with his then wife Jill in 1975. These days, the kitchen is overseen by son Jack (whose brothers Charlie and Edward look after wine and interior design respectively), which explains why it still has the feel of a family-run, family-friendly operation, albeit one that must be booked months ahead and saved up for. Some dishes seem inspired by Stein senior’s globetrotting TV career: mussels masala with coconut, ginger and green chillies, say, or an Indonesian seafood curry of cod, bass and prawns. But the best dishes are the simplest and allow diners to appreciate not only the quality of the produce (reassuring, given that most mains cost upwards of £40) but the skill of the cooking. Roast turbot is a signature here, firm white fish encased in a layer of crisp skin and with a delicacy of flavour that makes the citrussy hollandaise redundant; save it instead as a dipping sauce for thin-cut chips. Elsewhere, the menu changes depending on the catch from the boats morred up on the quay opposite. To start, snacks might feature some fresh seafood on ice: a Porthilly oyster with Cabernet Sauvignon vinegar and shallot dressing, say, or a fleshy langoustine tail to dunk into fresh mayo. Flakes of snowy-white crab are paired with intensely savoury brown meat and a saline wakame salad, while another gently Asian starter matches scallops with soy, ginger and spring onion. An 8oz steak is the lone meat option, though vegetarians fare rather better, with a dedicated menu showcasing veg sourced from the nearby farm of former Stein chef Ross Geach who, like so many of the suppliers – and customers – is a local with a long-standing relationship with the restaurant. Wines have been chosen with care, although prices rise rapidly from £30.

‘Evergreen’ is an appropriate descriptor for this Glasgow institution known simply by locals as ‘The Chip’. Established in 1971, you might think that tradition is the name of the game. Not so. Under the careful stewardship of the Clydesdale family, they pulled off the trick of subtly reinventing without losing authenticity or core values.

1973

At the other stylistic extreme is a restaurant with the unpromising name of the Ubiquitous Chip, in a tiny mews house just off the Byres Road, a raffish thoroughfare where the Bishop of Glasgow used to keep his cattle. There is a tasteful simplicity about the white-and-orange-washed brick interior, with a few targes for decoration, and Govancroft pottery on the plain wooden tables. The menu is cleverly arranged to make a modest celebration possible for the young and impoverished. Home-made soup, Shetland herrings Lorraine, brandy snaps and cream, and half a bottle of ordinaire from one of Byres Road's numerous off-licences, would cost about £1:50 a head. Smoked Lochgilphead mussels, marinated haunch of venison, and syllabub, almost double that price. The materials especially the beef and smoked fish - and the cooking are good, though cream is too much emphasised. A brave attempt to serve Hebridean carrageen mould, flavoured with whisky, seems to have foundered on political rocks: at least, supplies of carrageen come from Ireland, and have not arrived for months. A Guide inspector who used to eat this delicate dish in the Isle of North Uist during the war claims that cream and whisky would spoil it "milk freshly drawn from the cow should be used. It is nowhere near as good made with goat's milk. And in spite of the seaweed, it does not taste at all salt?

2022

In 1971, Scotsman Jackie Stewart secured his second Formula One world title and the Ubiquitous Chip opened in Glasgow's West End. A vintage year. It's Sir Jackie now, while the last half-century has seen the Chip leading from the front, flying the flag for Scottish produce. The covered courtyard of a one-time stables makes for a compelling centrepiece with its lush foliage and pond, while the word 'quirky' rolls off the tongue as readily as 'iconic' when describing the place. There's a roof terrace (the city's only rooftop bar, they say) and a couple of other bars, plus a brasserie and restaurant. The brasserie is on the first floor and favours a sharing approach with platters (East Coast Cured charcuterie, cured and smoked fish) and full-flavoured plates such as ox cheek with Parmesan polenta and baked Ayrshire beets with candied walnuts. The restaurant serves up a tasting menu if you're up for going full throttle; otherwise, stick to the carte where you can go from the Chip's own venison haggis, via Loch Melfort sea trout, to heather honey and oatmeal ice cream. Local ingredients may well anchor the menu, but this is modern Scottish cooking, so the kitchen turns the freshest mackerel into ceviche and serves it with oyster tempura, and partners hand-dived Barra scallops with saffron velouté and salt-cod fritter. Borders lamb arrives with little gnudi made with Crowdie (a soft cheese) and cured lamb, while vegetarians have well-considered options including a bespoke tasting menu. The wine list opens at £25 for a Catalonian white and Georgian red, and then heads off around the world where some serious options await. There are draught and bottled beers, too, or you could head to the Wee Whisky Bar for 'more whiskies per square foot than any other bar in Scotland'. Aye, we'll drink to that. The sale of this iconic Glasgow venue in July 2022 perhaps marks the next chapter as the new owners commit to build on the best of what is there.

Gastronomy Central in recent years, Bray is still a picture of an unruffled ancient English village, and the Waterside Inn was where is all started. Founded in 1972, the tone of the classic cuisine, first under Michel Roux, and now under his son Alain, barely changes from year to year.

1975

The Roux brothers spared no expense to turn this old pub, with David Mlinaric's help, into a restaurant whose floor-length sliding windows look on to the water (you may arrive that way if you choose). Visually, all the scene needs is Manet to paint it, and gastronomically, Pierre Koffman in the kitchen is already an artist of note. Indeed, one grateful customer suggests the place be nationalised so that everyone can enjoy it, but Mr Healey would find the price high and the Roux brothers easily affronted. Naturally, the prices and the firm's strong conviction of righteousness provoke criticism of any shortcomings: "The head waiter should not translate bar au fenowil as red mullet. Sauce or wine should not land on the tablecloth. Boiled potatoes should not be overcooked.' But an exacting test meal showed the place pretty well at its best, and would have been hard to surpass anywhere. M Koffman is a Gascon, and a sensitive fish chef. His pâté de poison à la Guillaume Tyrel (£1-60 as a first course) had a 'very thin brioche coating with tarragon and fennel overtones' and was served with a beurre blanc sauce. Butter, too, must have been the prime ingredient of the very pale and delicate leek and cream sauce for the salmon sausage - an undignified rendering, perhaps, of cervelas de saumon vallée de l'Adour (£1•85). This and other specialities are based on family favourites - for instance, tournedos Camille, with chicken quenelles and a genuine Périgueux sauce, and ragoût de volaille de Madame Cadeillan (£2-85). Vegetables on this occasion were à point. Fish soup, pigeon on occasion, cassoulet, and some deliciously refined sorbets are among many other delights mentioned. The tarte au citron seems over-rated to connoisseurs of lemon meringue pie, and someone has not yet mastered bread rolls. The wines are dear and not always worth it, but in middle ranges note, for instance, domaine-bottled Charmes Chambertin '66 and château-bottled Ch. Guiraud '66, both at &5 or so. Carafe Mâcon red or white or Languedoe wines are £2-£3. Prices are deliberately vague because they have not been supplied for 1975. It is possible for the unwary to pay £1:70 for a glass of '58 port. Music, and dancing, are possible sometimes.

2022

A landmark destination for 50 years and counting, this ‘citadel of classic gastronomy’ still has the power to captivate, not least with its Thames-side location – a willow-shrouded riverbank with birds twittering in the sunlight and boats swaying by their moorings. An English idyll you might think, yet this corner of a Berkshire village is forever France, suffused with unshakeable Gallic civility – although all that studied politesse can feel rather dated, especially since the departure of charismatic maître d’ Diego Masciaga back in 2018. From the very beginning, this ‘restaurant avec chambres’ has had Roux family blood coursing through its veins, with Alain (Michel’s son) currently upholding its deep-rooted traditions. He oversees a repertoire of exalted haute cuisine designed to please but never offend – respectful cooking with a proper sense of occasion, promising rich rewards for those who are prepared to forget about their bank balances for a while. Penny-pinching is not an option here. Fashions come and go, but the Waterside’s masterly rendition of quenelles de brochet (pike) with langoustines is a hardy perennial, likewise pan-fried foie gras with a thoroughly appropriate Gewürztraminer sauce – or even a boozy cocotte of oxtail and beef cheek braised to unctuous richness in Beaujolais. It may be entrenched in the grand old ways, but the kitchen also steps gingerly into the modern world – poached halibut dressed with strips of mooli and a piquant lime and vodka sauce or a gâteau of grilled aubergines with roasted quinoa, prunes and orange vinaigrette. Alain Roux is a master patissier by trade and the flurry of intricately fashioned desserts shows off his true vocation: don’t miss his soufflés (warm William pear with persimmon coulis, for example). ‘Wine suggestions’ start at £45 – the bottom line on a voluminous, scarily priced list that delves deep into the annals of French viticulture.